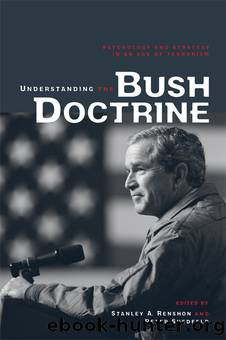

Understanding the Bush Doctrine: Psychology and Strategy in an Age of Terrorism by Stanley A. Renshon & Peter Suedfeld

Author:Stanley A. Renshon & Peter Suedfeld [Renshon, Stanley A. & Suedfeld, Peter]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9780415955041

Goodreads: 2050558

Publisher: Routledge

Published: 2007-01-01T00:00:00+00:00

Preventive Logic in American Foreign Policy since 1945

In the early years of the Cold War, American political leaders recognized that the U.S. atomic monopoly would be temporary and that the Soviet Union would soon develop the atomic bomb. They feared an adverse shift in the balance of power, believed that the Soviets were an implacably hostile and immoral adversary that was bent on world domination, and expected that the Soviets would probably go to war once they had the capability to do so. There was some talk about the strategy of prevention among U.S. decision makers and their advisors in the late 1940s, but uncertainty about whether the United States could actually win a war against the Soviet Union, combined with the belief that a preventive attack was inconsistent with American values and politically impractical, quickly silenced such talk. Instead of preventive war, the U.S. preferred a policy of massive rearmament, incorporated such a policy into NSC-68 (National Security Council, 1950), and adopted it once the Korean War created the political conditions that made it feasible to formally adopt that policy.41

American leaders gave more serious thought to the feasibility and desirability of a strategy of prevention in the 1950s, but they came nowhere close to adopting one.42 President Dwight D. Eisenhower, in a note to Secretary of State John Foster Dulles, asked whether âour duty to future generations did not require us to initiate war at the most propitious moment,â and raised the issue several times at meetings of the National Security Council in the 1952â54 period.43

In emphasizing that preventive logic was one of several factors leading the United States to take a tough line against the Soviet Union, Marc Trachtenberg suggests that a primary American motivation was to test the Soviet Union, to assess what its intentions really were, and to determine whether a war was inevitable. If the Soviet Union responded with a hard line even while they were weak, it would be reasonable to infer that they would be likely to take an even stronger line once the balance of power had shifted and the Soviets were in a stronger position. If that were the case, the U.S. could think more seriously about a strategy of prevention.44

This is an interesting argument, one that implicitly adopts a signaling model framework, but it is several steps removed from a strategy of prevention. The validation of that argument would require a lot more evidence that U.S. decision makers were thinking along these lines, that they would have been willing to seriously consider military action in the case that the Soviets had adopted a harder line, and at what point they would have done so. It is easier to speculate about how you might hypothetically act in such a situation than to actually make such consequential and irreversible decisions once you get there.45

Discussions about the viability of a strategy of prevention were more prominent in the Kennedy administration. During the Cuban missile crisis, American decision makers seriously considered the possibility of an air strike (surgical or more massive) against Soviet missile sites in Cuba.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

| Anthropology | Archaeology |

| Philosophy | Politics & Government |

| Social Sciences | Sociology |

| Women's Studies |

The Secret History by Donna Tartt(19086)

The Social Justice Warrior Handbook by Lisa De Pasquale(12190)

Thirteen Reasons Why by Jay Asher(8909)

This Is How You Lose Her by Junot Diaz(6886)

Weapons of Math Destruction by Cathy O'Neil(6279)

Zero to One by Peter Thiel(5801)

Beartown by Fredrik Backman(5754)

The Myth of the Strong Leader by Archie Brown(5507)

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin(5442)

How Democracies Die by Steven Levitsky & Daniel Ziblatt(5218)

Promise Me, Dad by Joe Biden(5153)

Stone's Rules by Roger Stone(5087)

A Higher Loyalty: Truth, Lies, and Leadership by James Comey(4962)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4925)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4788)

Secrecy World by Jake Bernstein(4753)

The David Icke Guide to the Global Conspiracy (and how to end it) by David Icke(4717)

The Farm by Tom Rob Smith(4507)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4490)